Come on, stumble!

The Amsterdam region is not meeting its climate targets. We want to be done with gas, be car-free, circular, clean – all without letting go of our obsession for grip, direction, our own agendas and demonstrable results. The current approach is clearly insufficient to achieve the objectives. How is that possible?

How to really start making transitions

A guest essay by the DRIFT institute

Amsterdam is the city of progress. Progressive politics is not only self-evident, but as a magnet for creatives, entrepreneurs and socially engaged people it is a source of innovation and inspiration. The embrace of the donut economy went all over the world, it is known worldwide as a city of bicycles and cultural innovation (and tolerance). Large businesses, knowledge institutions, governments and SMEs work together in the region to stimulate innovation and economic development. In this guest essay we observe, however, that all this hardly leads to structural changes or transitions. Over the past few years, DRIFT has looked at the state of the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area with the Amsterdam Economic Board, and the main conclusion is that the real challenges are still ahead of us.

Amsterdam is in danger of falling short of its own climate targets. The regional economy is largely linear and there is little structural policy that indicates that this will change quickly. In the next 30 years, 4800 streets must be free of gas, car-free, energy-positive and nature-based without a military plan, the necessary labor power being available or the population involved? at all brought. The gains made here and there with, let’s be honest, leading and inspiring projects and policies are negated by growth in consumption. In other words, the current path is completely insufficient to achieve the stated climate and biodiversity objectives.

How is this possible?

The implementation illusion

The explanation is as simple as it is confusing: policy and management. The way in which we tackle major societal challenges together and try to solve them through innovation ensures that we keep ourselves captive in the current systems and structures. Whether we look within the government or the business community: the dominant way of making policy is to look for solutions to specific problems from the existing situation: optimization. All kinds of specific departments and structures have been developed for this, within which there is a continuous search for control, efficiency and risk reduction. Whether it’s called scenario planning, strategy or process management: the aim is constantly to make the existing situation better (or less bad). Often with the best intentions, but ultimately mainly symptomatic relief that confirms the status quo by reinforcing it, reproducing it and investing even more in it. By trying so desperately to improve existing economic structures and processes, we simultaneously maintain them.

We see this phenomenon all around us: our milk production is polluting and must be sustainable, so Campina’s innovation department is starting a program on the way to planet proof . There is no fundamental discussion about the usefulness and necessity of a global dairy industry in a densely populated polder. Schiphol and KLM cause noise and air pollution, so they are urgently looking for more sustainable fuels and quieter aircraft. In the meantime, however, the evidence is mounting that sustainable aviation of this magnitude is not feasible before 2050. In order to achieve climate targets, shrinkage of this sector will also have to be discussed. Cars cause a lot of CO2 emissions, so we are massively encouraging electric driving, but both the number and size of cars are still growing. We want less waste but at the same time we keep using and inventing more complicated materials. This makes recycling and reuse an increasingly complex task. Why do have innovated up to 250 different types of plastic? The innovation this region excels in, actually constitutes a postponement of transition.

The basic reason for this is the way we analyze problems and think about solutions. Policymakers, administrators and managers are trained to exercise control, reduce risks, monitor stability and take responsibility for outcomes. The form that has been devised for this, project and programme management, has now become a separate discipline with its own internal control logic and procedures. Projects and programs are formulated, based on a social need and political priority. Subsequently these must spend (public) resources in a responsible and verifiable manner. In practice this means: quantitative and measurable goals, criteria for accountability and setting targets to make projects and innovations more manageable. After which projects often still go wrong or become more expensive .

This approach works well with regard to concrete implementation, but quickly becomes difficult when it comes to complex transitions. First of all, by isolating the problems, you make the other person less responsible. This applies to a government taking care of a ‘transition’ that can be favoured or opposed by a society. It also applies to a sustainability department managing a climate program, so that the departments of R&D or Finance (or in the case of authorities the Housing or Mobility Department) won’t need to take this on as a core task.

Secondly, the rational policy approach creates an illusion of manageability: everything is thought out. Integral goals, roadmaps and pillars are set (see, for example, the impressive ‘New Amsterdam Climate 2050’), while maintaining the idea that government and policy are the basis from which social development is directed.

Thirdly, this policy logic usually leads to the identification of innovations, new actions or interventions, often without identifying the tensions and uncertainties in progress and analyzing what should be stopped. This way of thinking and working leads to progress from the existing, but also negates the innovative forces from society and the sometimes double role that governments themselves play: guardian and part of the status quo versus the driver of progress and innovation.

Welcome to the transition twenties

This way, we are so caught up in a society in which there is increasing pressure to change course structurally, while the structures are insufficiently able to adapt. This pattern is historically far from unique and inevitably leads to shocks, crises and disruptions that lead to major social instability. From this transition perspective, we see signs everywhere that we are heading for such a period of institutional shift, if we’re not already in it. From a social point of view, climate, biodiversity, nitrogen and raw materials, but also care, education, housing and the labor market are complex challenges that will never be solved with policy: it is a process of muddling on from crisis to crisis. A growing undercurrent also no longer believes in the promises of the dairy industry, aviation industry, car industry, construction industry or large consumer companies to make current practices more sustainable and loses faith in the current course. The inability to transform quickly enough thus leads to increasing disruption and social and institutional instability. Some certainties of the past are already disappearing while it is still unclear and uncertain what the new normal will become. Think of the industries that we have attracted or retained in the Netherlands (steel, chemicals, greenhouses) with the promise of cheap, stable and reliable gas and electricity. This time will not return, and the alternative has not yet crystallized. Will it be CCS or green hydrogen? Biogas or full electrification? Or will (large) parts of the industry move to places in the world where renewable energy is abundant? This means a lot of uncertainty for citizens: we know the central heating boiler will need to go, but what should I replace it with and when? Each person having their own car is not future-proof, but what will our mobility system look like in ten years’ time? We’re going to stumble forward to find out. We do know one thing for sure: we’re in for a bumpy ride.

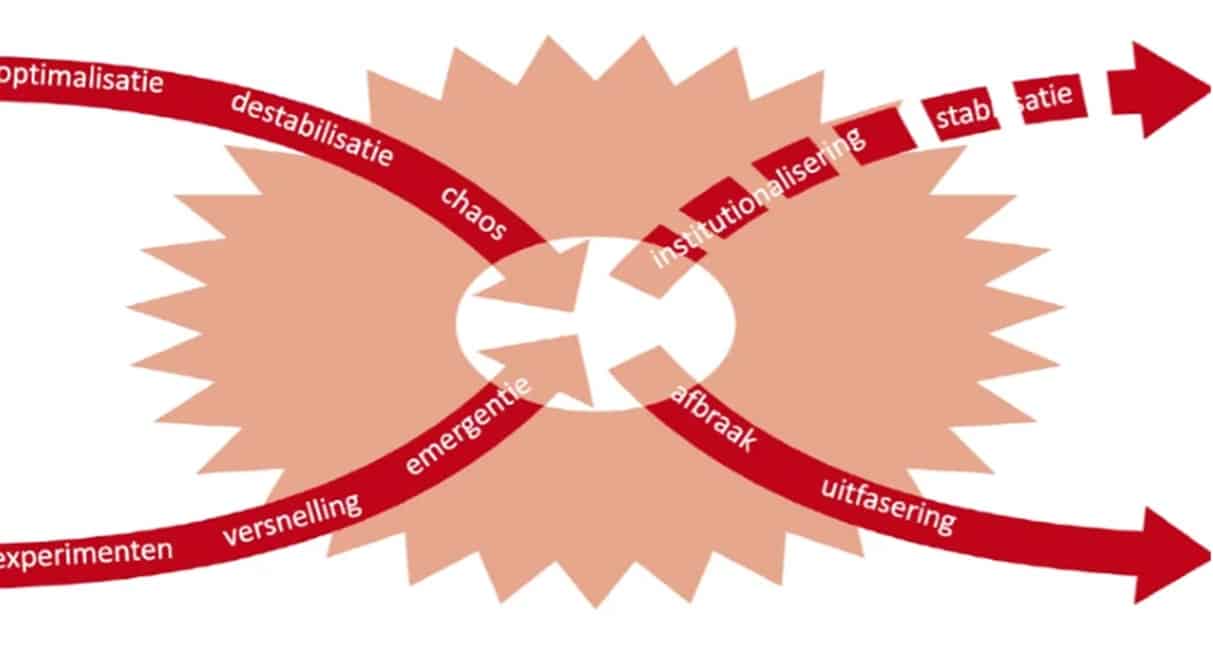

Against the background of the institutional struggle, another movement has emerged in recent decades: enterprising civil servants, social entrepreneurs, activists, idealists, researchers and inventors who have set to work with radically different ideas, practices, models and working methods. Try something different instead of improving. Instead of implementing, learn by doing. And instead of letting you check ‘to arise’. They do this from a radical vision: a future without fossils. A directly democratic economy that is circular. Fair mobility with the least possible use of space. A food system that is healthy and contributes to nature restoration. Gradually, these kinds of alternatives become less and less alternative and what has been the norm for so long becomes less and less self-evident. Perhaps even more so in the Amsterdam Metropolis. These interacting dynamics of build-up and breakdown are a characteristic of transitions as shown schematically in figure 1.

We are therefore beyond the initial phase of transition: accelerating alternatives, the status quo is increasingly under discussion. Our analysis from a transition perspective is that we’re entering a new phase in which space opens up for much more radical, accelerated and fundamental shifts. No longer is there a struggle of innovators against established parties. We see this also reflected during our work for the Amsterdam Economic board. Both the government and the business community are discussing the future, direction and their own role in this – sometimes internally, sometimes at the center of the public debate. This creates a space (physical, financial, mental, institutional) in which innovators and established parties struggle together for radical system change.

“Dealing with transitions, in short, requires a completely different way of thinking and working: it requires stumbling forward from a radical vision of desired transition.”

Derk Loorbach Professor Socio-economic Transitions Erasmus universiteit Directeur DRIFT

Radical change with the regime

When this process of shifting out of balance is set in motion, it is irreversible and can go in any direction. The uncertainties are maximum, control is minimal and the predictability and stability of the past are gone. If, in that context, the outlined approach to control and management remains the only response, undesirable outcomes are guaranteed. Either those in power and importance know how to use the momentum to consolidate their position and manipulate the transition, or such chaos ensues that social unrest and economic breakdown occur. In short, dealing with transitions requires a completely different way of thinking and working: it requires stumbling forward from a radical vision of the desired transition.

Of course, there are plenty of visions, policy agendas and strategic documents, but by a radical vision of transition we mean fundamentally questioning current structures and interests and using the transition momentum to say goodbye to everything that keeps us rooted in the current unsustainable economic environment. model: an economy based on consumption, with everyone having their own car in front of the door, (several) flying holidays in a year and a glass of milk every morning. That comes close: it concerns our own habits, but the government itself is also a major shareholder in the linear, fossil BV Netherlands, just like the companies and the employment they create. the realization that transition also means saying goodbye is starting to sink in: more and more established parties are under so much pressure that they sometimes have to or in some cases proactively shape their own transition from their own leadership.

In this context, especially within the Amsterdam region and from the Amsterdam Economic Board, we see the opportunity to no longer move ahead with the handbrake on, but to stumble forward by embracing radical transitions. This means explicitly focusing on radical transitions that in themselves also mean bidding farewell to everything that is now unsustainable, fossil, linear and unjust: a regenerative food system, mobility without private cars, a built environment that is positive for nature. In order to explore an economy in which we use as few raw materials and scarce (public) resources as possible, while restoring nature and shaping an economy that is just for as many people as possible. Without being able to outline exactly what that will look like, what it will cost and how we will achieve it. But we do know that there are frictions, resistances and risks in that process: with consumers who are given less freedom, with companies that will have to or will disappear at an accelerated rate, with politicians who will be asked difficult questions.

The concrete first steps are obvious: by choosing for Mobility as a Commons, instead of Mobility as a Service. Shared mobility to serve the community instead of a new revenue model for investors and companies – combining this with a radically different layout of public space. Or by embracing shrinkage, and all the uncertainty that comes with it, as the most realistic sustainability strategy for aviation. Or mobilizing social innovations and initiatives to lead the transition to a fossil-free built environment. Or focusing on as much local ownership and control over public facilities and decision-making as possible. In short, we’ll need to enter this process together, by leaving the undesirable, existing interests behind. By phasing out routines and structures that do not work and that keep us stuck in growth and consumption. At the same time choosing for a radical vision by building the new economic social structures and systems that are nature-positive, circular, democratic and just.

Stumbling forward as a strategy

We will elaborate on this in subsequent essays, both a policy strategy that focuses on social innovation and uses it to mainstream what now seems radical and unlikely, and a policy strategy that responsibly shapes phasing out. But we would like to end here with four recommendations that we hope all actors in the Amsterdam metropolitan region, supported by the Amsterdam Economic Board, will implement enthusiastically in the coming years.

A non-negotiable sense of urgency: We are in a climate and biodiversity crisis and despite all the progress our current efforts are insufficient.

Embracing and shaping a radical transition agenda: not making the existing more sustainable, but shaping alternatives that still seem radical and unlikely from a vision of desired transitions, and breaking with existing unsustainable practices.

Recognition of and support for existing transition practices in society: the people, entrepreneurs, activists and policymakers who have long embraced and shape radical transitions and show that it is possible.

Embracing stumbling blocks in policy and management: Instead of improving, try something different. Instead of implementing, learn by doing. And instead of controlling let it arise.

The question is whether organizations in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area are prepared to embrace this agenda. We often attribute their inability to change to unwillingness or ignorance. In the future it will become less and less unwillingness, but disbelief. A lack of imagination and creativity because we can’t imagine that more radical alternatives will actually ever become mainstream. From a transition perspective, however, it is impossible to niet to see that transformative change over time is inevitable: the urgency surrounding climate change and loss of biodiversity will only increase. With the transition twenties well underway the need has now arisen to let this go. It is now more radical to think that everything stays the same but sustainably, instead of embracing more radical transition paths.

We are curious what the essays will bring about in the network. That is why we submitted this essay to Nina Tellegen (Managing Director Amsterdam Economic Board) and Erik Versnel (Director Rabobank Amsterdam Metropolitan Area).

This essay calls for stumbling forward, in other words letting go of the urge for control and manageability. Nina endorses this recommendation: “We need to get away from the current culture of control and cramping, such as keeping drivers too far from the wind .”

“For banks, this represents a significant cultural shift”, says Erik. “After all, risk reduction is our core competence. But sometimes you need to get moving without knowing the end point. The path is created by walking on it.”

How can we let go of that urge for control? Nina: “Dare to stumble forward! We innovate and therefore make mistakes. We need to reflect on that.” Eric adds: “Dare to experiment. For example, we tried to buy Eneco. This was uncharted territory for us. And while it didn’t work out, that purchase attempt has convinced us that we want to become the banker of the energy transition.”

Nina does question the statement that innovation in the region stands in the way of the transition: “There I fundamentally disagree. Take initiatives such as AMdEX, neighborhood ehubs, reuse of solar panels against energy poverty. Some already big, others still in the stumbling phase on their way to a bigger step. I will highlight the LEAP initiative which shows that data servers can easily achieve 10% energy savings. Immediately! This is an incremental innovation within the current system, but taking the first step together means that you create support, that you get people on board and then work together on more radical solutions. With LEAP, we have therefore succeeded in forming a coalition with major players such as Microsoft, KPN, Dell, Rabobank, Schiphol, but also with startups, scientists, photonics companies that are already working on radically different ways of storing data. This requires much less energy consumption, or energy can be reused to heat houses, for example. I strongly believe in the combination of those two routes: taking the apparently small steps brings parties together to work on radical change. That is why I believe in an organization like the Amsterdam Economic Board, because we bring those different parties together.”

Erik also questions the radicality and activism of transition. “I endorse the recommendation that the transition should be accelerated and that the urgency is simply not up for discussion. But a transition takes a big jump from A to E, while we also need to pass by B, C and D. We cannot suddenly stop. We need to include customers in the transition. Activism is sometimes necessary to wake us up. But if the vision of the future is too far away, the step becomes too big to commit to.” Nina adds: “Radical means that you lose contact with each other and that you can’t do anything with it anymore because it simply exceeds the imagination. It may be idealistic, but we must continue to engage in dialogue and take common and realistic steps. The added value of the polder is that you stay in touch with each other and make progress together.”

The term ‘radical’ or ‘radical vision of the future’ can therefore also have a paralyzing effect. Then it becomes so radical that you can no longer do anything with it. “We do see the importance of the joint future perspective,” says Nina, “ and as the Amsterdam Economic Board, we also want to pay more attention to the question of what the desired future picture is now.”

19 April 2022

Read more about

Contact us

Want to keep up to date?

Get the best regional news and events (in Dutch) via the Board Update newsletter

Share this news

Want to keep informed?

Follow us daily on LinkedIn and sign up for the Board Update newsletter.

Read more

- Pressure on health care is increasing due to rising costs, an aging ...

- Reinforcing the power grid could solve grid congestion. But who will lay ...

- Three groundbreaking healthcare innovations have been selected to participate in the regional ...